What I like most, in Volume 15 of The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, is how Einstein grapples with the intellectual challenges he faces and how he uses more solvable problems as a mental salve.

When faced with apparently insurmountable fundamental problems in theoretical physics, such as the unification of gravitation and electromagnetism, or the wave-particle dualism of light, Einstein's only hope to find a light at the end of tunnel was to turn toward experiments and observation.

In the case of unification, he proposed to check whether rotating neutral bulk mass has a peculiar electric charge, a "ghost" charge, which could possibly reveal a deep connection between mass and electric charge. In this, he received help from the experimental physicists Teodor Schlomka and Peter Pringsheim.

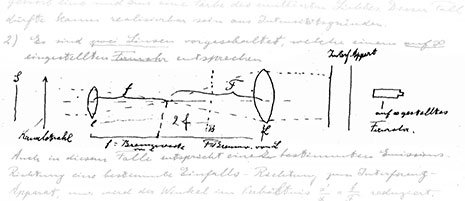

In the case of the corpuscular or wave nature of light, he proposed an experiment that would decide whether excited atoms emit light instantaneously (in quanta), or in a finite time (in waves). Einstein expected quantum emission to be confirmed. In this, the experimentalist Emil Rupp gave him a hand – and in the process forged his experimental findings to please Einstein. Rupp repeatedly wrote that he had experimentally proved what Einstein wanted to see, and Einstein responded with detailed criticism, pointing out how the experimental setup ought to be modified before the results could be trusted. Einstein came to believe that the experiment proved that the wave theory prevailed after all. Colleagues criticized both Einstein's proposed experiment and the data. (For more detail see: "Of Waves and Particles: The Emil Rupp Affair", Section VII of the Introduction to Volume 15 of The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, available here.)

The light at the end of the tunnel remained as elusive as before.

But Einstein continued to be interested in various useful gadgets, such as constructing refrigerators, a project he engaged in with Leo Szilard. These preoccupations look, to me, like periods of relaxation meant to relive his days at the Bern patent office 20 years earlier, where as a young man he had rocked the cradle of relativity.